I reserved the county’s one copy of Noel Streatfeild’s Tennis Shoes from the public library nearly three months ago, but it’s been checked out to some snot-nosed wannabe Federer since January with no return in sight, so it looks like my last 1937 Club offering will be Edward Anderson’s thriller Thieves Like Us. In my day you paid dearly if you were one day late, but in 2024 Cambridgeshire County Council doesn’t even bother to levy fines on children’s books. Where’s the incentive for any child to return any book ever? It occurs to me that a few months on an Okie prison farm would do this punk a world of good. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

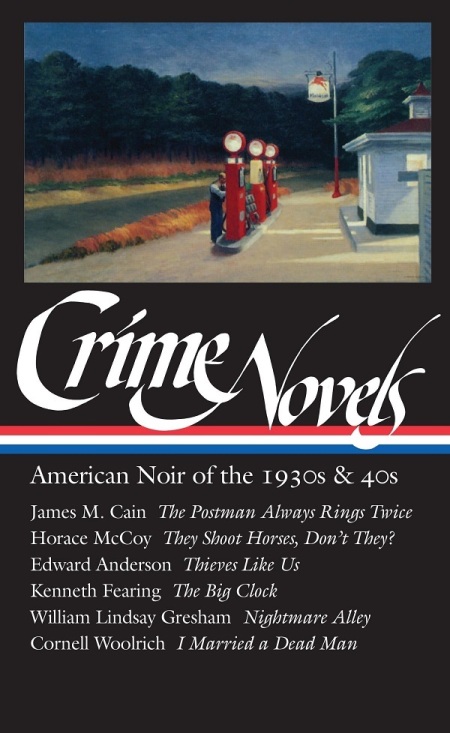

Don’t you covet Library of America editions? If you gave me the option of owning the entire back catalogue of any one publisher (big if), they’d be in with a very strong shout. Anyway, the title Thieves Like Us meant nothing to me, though the novel turns out to have been the basis of a film I’d seen, 1948’s They Live by Night, the directorial debut of Nicholas Ray (of which more later), and one I haven’t, Robert Altman’s 1974 Thieves Like Us (which looks worthy of inspection).

So what about these thieves? Do they really like us, or is it just a clever title? Well, there are three of them: T-Dub, Chicamaw and Bowie (they sound like the ChatGPT version of TLC; sorry, I will start being serious soon, probably). They’ve just escaped from an Oklahoma prison and are about to hold up a car and make their getaway. Anderson’s cool, economical style means you have to pay attention to work out who’s who and what’s going on, but if you’re Thick Like Me there’s often a newspaper report just around the corner that will confirm you got right what you just read (or not) and fill in some extra details.

ALCATONA, Okla., Sept. 15—The escape of three life-term prisoners who kidnaped a taxicab driver and a farmer in their desperate flight was announced here tonight by Warden Everett Gaylord of the State Penitentiary. Combined forces of prison, County and City officers were looking for the trio. The fugitives are:

Elmo (Three-Toed) Mobley, 35, bank robbery; T.W. (Tommy Gun) Masefeld, 44, bank robbery; and Bowie A. Bowers, 27, murder.

On one level this book is a thriller about three men on the lam doing a series of bank jobs; on another, a Bonnie and Clyde-style doomed love story; on another, social commentary. The phrase ‘thieves like us’ pops up a few times, usually to describe the haves compared to the have-nots, or straight people compared to criminals.

“You know what that banker would have done if you hadn’t of got onto that slip,” T-Dub said. “He’d of squawked that he had been robbed of it all just the same. There’s more of these bankers than you can shake a stick at that’s got it stacked around over their banks and just praying every day to be robbed.”

“Sure,” Chicamaw said.

“They’re thieves just like us,” T-Dub said.

Most of the story is told from Bowie’s perspective, and the reader is encouraged to like him: he’s the youngest of the trio, the most aspirational, the one who when he’s got $5,000 salted away plans to give up the bank robberies and settle down. And he is a nice guy, to the point of being callow: when one of his buddies gets caught and ends up on a prison farm, he hatches a plan to spring him by means of a very risky subterfuge. But how far can your sympathies stretch? If this isn’t exactly the Dust Bowl world of The Grapes of Wrath, it’s close. Is it better to be a desperate doormat or a desperate outlaw? You can certainly have sympathy for a thief, especially when he’s been through something inhuman –

Lightning slashed the swirling heavens. Maybe a man saw something like that when they kicked the switch off on you in the Chair, Bowie thought. It didn’t seem like no nine years since that morning when his lawyer came and told him they weren’t going to burn him. Maybe though he had died back there in the Chair? This was just his Spirit out here in this rain? In this old world, anything happened.

– then a news report with a sentence like ‘A police benefit here last night for the widows of the two slain officers netted $320’ pulls you up short. $320 raised by decent poor people, while Bowie’s sitting pretty on thousands. Something’s not right.

(An aside: you can add this to Rose Macaulay’s I Would Be Private as a novel that alludes to the Dionne quintuplets. You couldn’t move for those dames in the mid-1930s.)

They Live by Night, which I revisited, is an interesting adaptation of the book that contains some seeds of the superior melodramas Nicholas Ray would go on to make in the 1950s, with the focus largely on the relationship of Bowie (Farley Granger) and his girl Keechie (lovely Cathy O’Donnell). Preserved, happily, is Anderson’s stylish habit of omitting the bank robberies and letting us piece them together in the aftermath; jettisoned, sadly but understandably, is some of the bleakness of the ending. What hits hardest about Anderson’s book is its conclusion, presented once again as newspaper reportage. The contrast of the dispassionate journalistic portrayal of Bowie with the reality of his life as presented in the 200 or so previous pages is pleasingly provocative. He’s more like us than many of us would like to admit.

***

Thanks once more to Simon and Kaggsy for organising the 1937 Club, and thanks to everyone else for reading and commenting. This time and last time I’ve gone kinda overboard, and I dare say I’ll be doing it again in a few months, all being well. Until then.